CULT MOVIE RESEARCH:

A Bit of Cult Context

If we are to believe most critics, originally, the term ‘cult film’ was reserved for long-term commitments of fringe audiences to ‘small’ movies at the edges of culture. They often bombed, a few were never properly released at all; they often offended, some were banned; they were often bad, or badly made, or both.

It is under this now classic description that the term cult gained prominence, especially under the format of midnight movies such as El Topo, Night of the Living Dead, Pink Flamingos, The Harder they Come, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and Eraserhead. Old forbidden fruits such as Freaks and Witchcraft through the Ages, or Un chien andalou were also given new life thanks to midnight movie screenings.

In recent years, however, The Lord of the Rings, Titanic, The Dark Knight, and Pirates of the Caribbean have also been claimed as cult films. Not because they were popular, or at least not only because they were big successes.

Rather, could it be they were claimed as cult in spite of their popularity? Could it be they are cults because they were based on cult novels and comic books, or even historical disasters (there is such a thing as the Titanic cult) and theme park rides (and aren’t pirates a cult in themselves?), or because a star died eerily?

The fact that these films had an already existing, highly developed fan base may have also helped them achieve cult status.

What is the difference between the two kinds of cults sketched above? Is one more cool, and the other more hot? Is one more authentic because it is ‘older’? Is the more recent kind more authentic because it reflects the cults of our times – and not some bygone era’s?

Where lies the truth? Probably somewhere in between Or, is it, as they say in The Rocky Horror Picture Show, ‘just a jump to the left?’

Because we academics like to be precise we would like to find out exactly.

Lists and Opinions of Cult Films

Lists and Opinions of Cult Films

What do other people think?

There are many lists of classical and canonical cult films in circulation. And there are many views on what makes a cult film. Check out the following:

- Entertainment Weekly and 5MTL list their top 50 of cult films.

- BBC cult film definition. With special focus on Kill Bill.

- Filmsite’s comments on cult films.

- The book series Cultographies’ top 111 of cult films.

- Screening the Past on cult films and post-cult films. With special focus on Donnie Darko.

- An article from The Vancouver Sun on cult fandom. With a special focus on The Dark Knight.

- An article from Silverchips.online on cult film.

- A top-25 of cult films at Boston.com.

- The community of Epinions on their favorite cult films.

- Read Michael Newman's thoughts on cult in the digital age.

The Cineaste Cult Symposium

The Cineaste Cult Symposium

What do professional critics think? Or our colleague academics?

What do professional critics think? Or our colleague academics?

The film magazine Cineaste organized a symposium on cult cinema.

- Read the editorial opinion of the Cineaste staff.

- Read the views of David Church, Matt Hills, IQ Hunter, Chuck Kleinhans, Mikel J. Koven, Ernest Mathijs, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Jamie Sexton and Jeffrey Weinstock.

- Read the views of Joe Bob Briggs, J. Hoberman, Damien Love, Tim Lucas, Danny Peary, Jeffrey Sconce, and Peter Stanfield.

- The essay by Elena Gorfinkel ‘Cult Film or Cinephilia by Any Other Name’ from Cineaste.

- Adrian Martin’s essay ‘What's Cult Got To Do With It?: In Defense of Cinephile Elitism’ in Cineaste.

Cult Film Definition

Cult Film Definition

And of course there is a full-blown definition of cult film. Here it is, as it appears in The Cult Film Reader, and on the Cultographies website.

The Short Definition:

A cult film is characterized by its active and lively communal following.

Highly committed and rebellious in their appreciation, cult audiences are frequently at odds with cultural conventions – they prefer strange topics and allegorical themes that rub against cultural sensitivities and resist dominant politics.

Cult films transgress common notions of good and bad taste, and they challenge genre conventions and coherent storytelling.

Among the techniques cult films use are intertextual references, gore, loose ends in storylines, or the creation of a sense of nostalgia.

Often, cult films have troublesome production histories, coloured by accidents, failures, legends and mysteries that involve their stars and directors.

In spite of often-limited accessibility, they have a continuous market value and a long-lasting public presence.

![]() The Somewhat Longer But More Precise Definition With Examples:

The Somewhat Longer But More Precise Definition With Examples:

A cult film is defined through a variety of combinations that include four major elements:

- Anatomy: the film itself – its features: content, style, format, and generic modes.

- Consumption: the ways in which it is received – the audience reactions, fan celebrations, and critical receptions.

- Political Economy: the financial and physical conditions of presence of the film – its ownerships, intentions, promotions, channels of presentation, and the spaces and times of its exhibition.

- Cultural status: the way in which a cult film fits a time or region – how it comments on its surroundings, by complying, exploiting, critiquing, or offending.

We do not propose that all of these elements need to be fulfilled together. But we do suggest that each of them is of high significance in what makes a film cult.

The Anatomy of Cult Film

There are some features that tend to be associated with cult films more than others. The first is Innovation. Cult films contain an element of innovation, aesthetically or thematically; they challenges conventions and instigate new techniques. Contrary to films that insert small and careful innovations to avoid upsetting viewers, cult films are shocks to the system. Many extremely progressive ‘arthouse’ films have gained a status of cult. Examples include Un chien andalou (1928), Salo (1975) Le weekend (1967) or In the Realm of the Senses (1976).

A second quality is Badness. Cult films are often considered bad, aesthetically or morally. Of particular interest are those films being valued for their ‘ineptness’ or poor cinematic achievement, which places them in opposition to the ‘norm’ or mainstream in that they attain a status of ‘outrageous otherness’. ‘Bad’ films quickly gain a status as cult (though far from all ‘bad’ films achieve that status). Examples are Reefer Madness (1934), Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959), or Showgirls (1995).

Transgression goes beyond the basic poles of good and bad. A lot of the competence of a cult film lies in its ability to obliterate any possible comparison with any other films – so they are not better than others, nor worse, they are off the planet. This involves ignoring 'conventions' of filmmaking, which may include stylistic, moral, or political qualities, either through crudeness (Thundercrack, 1975) or inventiveness (Eraserhead, 1977). Transgression often connects cult cinema with US avant-garde cinemas, like the films of Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and the Kuchar Brothers. It also relates to unusual films like El Topo (1970) or The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975).

Cult films are often made within the constraints and possibilities of Genre, and as such they adhere to well-structured regimes of production. Yet they blur and push the generic conventions by mixing genres (Alien, 1979), exposing and/or mocking a ge-nre’s unwritten rules satirically (Blazing Saddles, 1974) or hyperbolically exaggerating those rules (Barbarella, 1968). Instead of taking culture seriously, cult films carnivalize culture, turning it into one big uncontrolled mess. The most popular genres that lend itself for these treatments are horror, science-fiction, and fantasy because of their utopian and dystopian opportunities (Blade Runner, 1982; Labyrinth, 1984); and melodrama and musical because of their overplaying of the emotional states of characters and situations (Gone With the Wind, 1939; Sound of Music, 1965). Often, generic styles are upset by the use of decidedly artificial motives. Surrealist imagery and deadpan existentialist performances are favourite techniques (The Blues Brothers, 1980; The Big Lebowski, 1998).

Cult films are Intertextual. They invite comparisons, connections, and linkages with other films and other parts of culture. This involves the inclusion of references to other film texts in the form of quotes or cameos but also the calling into reflection of cultural myths, historical backgrounds, and archetypes. At its most subtle, intertextuality offers playful inside jokes for avid audiences. Good examples are the layers of references in From Dusk ‘till Dawn (1995) or Ginger Snaps (2000). Exquisite use of intertextuality puts cult films at the centre of fashions, such as swinging London in Blow Up (1966), hippiedom in Easy Rider (1969) or Generation X in Slacker (1993), making them a true ‘testimony of the times’. At its extreme, intertextuality turns the story into a direct address of films or media, like in Videodrome (1983).

Many cult films leave room for narrative and stylistic Loose Ends: the impression the film is unfinished. Abrupt, insultingly conformist, or dissatisfying or puzzling endings are good examples of loose ends. They are also typical for scenes that show obvious signs of inclusion, or deletion of material at a later stage (caused by censorship, studio interference, wear, or force majeure). Loose ends violate continuity, disrespect narrative cohesion (either a sign of integrity, incompetence, or of selling out). Ironically, these interventions become badges of honour. They give viewers the freedom of speculating on the story, and polishing or radicalizing the style on the film’s behalf. It puts hilariously bad movies (Maniac, 1934) shoulder to shoulder with films that received harsh censorship treatments (Last House on the Left, 1972), and films whose story is simply too complex or convoluted for a straightforward narrative (2001, A Space Odyssey, 1968).

![]() A core feature of many cult films is their ability to trigger a sense of Nostalgia, a yearning for an idealized past. The nostalgia can be part of the film’s story. Humphrey Bogart’s remark, in Casablanca (1942), that he and Ingrid Bergman will “always have Paris” is perhaps the best example. But most likely it is an emotional impression. Much of the cult reputation of Sissi (1955-1957) and The Sound of Music (1965) relies on their ability to evoke nostalgia for the glamour and picturesque scenery of traditional Austria, encapsulated in the cities of Vienna and Salzburg (which have since becomes sites of pilgrimage for fans). Cities oozing grandeur, such as Rome (Roman Holiday, 1953) or Venice (Don’t Look Now, 1973) add to films’ cult appeals. Painstakingly authentic historical epics, such as Das Boot (1981), while not evoking nostalgia in the same way, also draw a lot of their cult appeal through their ability to submerge audiences in a ‘past world’.

A core feature of many cult films is their ability to trigger a sense of Nostalgia, a yearning for an idealized past. The nostalgia can be part of the film’s story. Humphrey Bogart’s remark, in Casablanca (1942), that he and Ingrid Bergman will “always have Paris” is perhaps the best example. But most likely it is an emotional impression. Much of the cult reputation of Sissi (1955-1957) and The Sound of Music (1965) relies on their ability to evoke nostalgia for the glamour and picturesque scenery of traditional Austria, encapsulated in the cities of Vienna and Salzburg (which have since becomes sites of pilgrimage for fans). Cities oozing grandeur, such as Rome (Roman Holiday, 1953) or Venice (Don’t Look Now, 1973) add to films’ cult appeals. Painstakingly authentic historical epics, such as Das Boot (1981), while not evoking nostalgia in the same way, also draw a lot of their cult appeal through their ability to submerge audiences in a ‘past world’.

A trope often appearing in combination with nostalgia is Time-Travel. Because it creates loose ends and defies logic and cohesion of narration and space-time continuity, it is an ideal technique for cult films. It allows for visualizations of past, future, or a parallel present, and it is a guaranteed way of generating speculation on how to interpret the story, and where (and when) it belongs, as evidenced by the cult followings for Donnie Darko (2001), Back to the Future (1985), and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

‘Yukkie stuff’ or Gore is a sure way to grant films a cult status. This not only relates to films that transgress on the level of explicit violence or presentation of uncomfortable materials (like horror films), but also to films whose content and style invokes a sense of ‘impurity’ or ‘endangerment’ of the human body’s physical integrity, in the sense that they contain explicit violence, decay, mutilation, or cannibalism and they involve lots of fluids that cross the border between the inside and outside of the body: tears, sweat, spit, urine, blood, pus, and other excretions. Examples are The Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes (1971), and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), or the gory special effects of Evil Dead (1982), The Thing (1982), and Scanners (1981).

The Consumption of Cult Film

The emphasis of cult films is not on box-office figures and mass audiences. Nor do cult films rely too heavily on the critical acclaim so essential for art-house and independent cinema. Their reception does not typically end at the vaults of a bank or the archives of a museum of heritage. Instead, it relies on continuous, intense participation and persistence, on the commitment of an active audience that celebrates films they see as the opposite of ‘normal and dull’ cinema.

Active Celebration is essential. It comes indeed close to the organised forms of religious or spiritual worshipping of the original meaning of the term ‘cult’. As with traditional cultism, cult cinema reception relies on rituals of celebration, sometimes with hierarchical orders imposed on the activities, and with fairly strict delineations for roles in the ceremonies. As with most rituals in society, aspects of purity, initiation, and infection play a crucial role in this celebration.

The sense of Communion and Community to be experienced at cult film events might be described as pre-programmed, and sometimes even semi-automatic, as reports on Rocky Horror Picture Show stagings and Sound of Music singalongs indicate, but it is equally possible to see it as more spontaneous, as an unplanned or even imagined sense of camaraderie and fellowship before, during, or after a screening. The way audiences have described their sense of belonging to a group after having seen the avant-premiere of The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003), or a rare screening of One Second in Montreal (1969), are good examples of this.

What all cult film consumptions have in common is that they are ‘Lived’ Experiences, either physically, or by proxy. Many celebrations of cult movies are live-events, within an atmosphere akin to theatrical performance, in which ‘being there’ and ‘being part’ become important. The element of physical endurance of some cult celebrations, like full-length screenings of Empire (1964), marathons of the Heimat series (1984), the timing of the original ‘midnight movies’ (literally at midnight), festivals’ all-nighters, or intimate ‘sleepover’ viewings, enhances films’ status to the level of cult, as a rite involving debutantes, survivors, and veterans. You will certainly remember a film differently after such an experience.

The consumption of cult cinema demonstrates a continuous Commitment. It is not a fad or craze. Once bitten, the bug stays. The most commonly known commitment is fandom. Cult films have dedicated fans, and the many fan conventions, associations, and formations involving cult movies, from the highly organised Star Wars fans, over the loosely organised Exorcist devotees, to the private fandoms of erotic thrillers testify of this. But at the same time there is a sense that the term fandom is too generalist and tame to actually capture the particular kinds of persistence and dedication involved in cult. Perhaps the difficulty of cult fandom is that it always needs to be of an offbeat kind. So, it is not the huge numbers of fans that might make Titanic (1997) cult but rather the way in which it was celebrated through all-girl repeat viewings. Traditional fandom remains largely respectful towards the film’s integrity but other ways of commitment involve challenges to its interpretations, either by robbing it of its meaning, or by replacing it by one that might counter its intentions. The ‘outing’ of Top Gun (1986) as a reportedly closeted gay film is a good example of how this appropriation can fulfil political purposes; in this case unmasking the homo-erotic subtexts in an otherwise very macho film. The more this happens for one film, the more likely it will become a cult film.

![]() Audiences of cult movies stress their Rebellious Attitude, and they frequently consider themselves outsiders, renegades roaming the borders of what is morally acceptable. Often this attitude exhibits itself in a fierce and radical refusal to condone regular movie-going, and in a penchant desire to disrupt such practices, for instance by inappropriate behaviour, such as disturbing sounds or ‘call and response’ reactions. A most peculiar example of this is the Brussels International Festival of Fantastic Film, where premieres, award ceremonies, and revivals alike are greeted with boisterous audience behaviour. Among the rebellious attitudes, cinephilia is the best known. Cinephiles are viewers who pride themselves on expert opinions on the topic of cinema. They have a preference for films that ‘challenge’ and/or contain ‘philosophical journeys’ – an appreciation for films that are ‘demanding’. Examples of films that are known to attract cinephiles are A Clockwork Orange (1971), Crash (1996), and Fight Club (1999). Buffs are the extreme opposite of cinephiles, revelling in their appreciation and trivial knowledge of almost every single film. Cinephilia and buffery come close to cultist consumption because of the way their extreme nature of appreciation challenges traditional forms of liking or disliking films. In between, Avid or smart audiences combine in-depth factual and theoretical knowledge about films with an informed understanding of narrative and stylistic sophistication. They revel in the number of references, interpretations and connections their knowledge allows them to make and by doing so they equip films with multiple subtexts. They do not usually make the harsh and detached aesthetic judgments cinephiles make. Kill Bill (2003-2004), Ginger Snaps (2000), and Japanese manga films have attracted such consumption; and manga’s punk-like fans (the ‘otaku’), or Ginger Snaps’ feminist Gothic following are good examples of avid audiences – in a sense these are relentlessly reflexive audiences for relentlessly reflexive films.

Audiences of cult movies stress their Rebellious Attitude, and they frequently consider themselves outsiders, renegades roaming the borders of what is morally acceptable. Often this attitude exhibits itself in a fierce and radical refusal to condone regular movie-going, and in a penchant desire to disrupt such practices, for instance by inappropriate behaviour, such as disturbing sounds or ‘call and response’ reactions. A most peculiar example of this is the Brussels International Festival of Fantastic Film, where premieres, award ceremonies, and revivals alike are greeted with boisterous audience behaviour. Among the rebellious attitudes, cinephilia is the best known. Cinephiles are viewers who pride themselves on expert opinions on the topic of cinema. They have a preference for films that ‘challenge’ and/or contain ‘philosophical journeys’ – an appreciation for films that are ‘demanding’. Examples of films that are known to attract cinephiles are A Clockwork Orange (1971), Crash (1996), and Fight Club (1999). Buffs are the extreme opposite of cinephiles, revelling in their appreciation and trivial knowledge of almost every single film. Cinephilia and buffery come close to cultist consumption because of the way their extreme nature of appreciation challenges traditional forms of liking or disliking films. In between, Avid or smart audiences combine in-depth factual and theoretical knowledge about films with an informed understanding of narrative and stylistic sophistication. They revel in the number of references, interpretations and connections their knowledge allows them to make and by doing so they equip films with multiple subtexts. They do not usually make the harsh and detached aesthetic judgments cinephiles make. Kill Bill (2003-2004), Ginger Snaps (2000), and Japanese manga films have attracted such consumption; and manga’s punk-like fans (the ‘otaku’), or Ginger Snaps’ feminist Gothic following are good examples of avid audiences – in a sense these are relentlessly reflexive audiences for relentlessly reflexive films.

![]() The final step in cult movie consumption is the construction of an Alternative Canon of cinema, pitched against the ‘official’ canon. Cult moviegoers not just consume but also champion a particular kind of film. This championing demonstrates itself in a variety of ways, but lists (see our own top 111 and personal top 25) are a typical characteristic of this. The Psychotronic Movieguide and numerous Cult Movies collections are key examples, as is the way in which a magazine like Fangoria established a canon in the 1980s. List-mania, to be found on virtually all websites devoted to cult cinema (and now in rapid adoption by online retailers) is the most visible feature of the alternative canon and partisanship of taste typical for cult cinema reception. Significantly, a lot of the canonizing is done amateurishly: in semi-communal circles (nerd circles, governed by rituals and exclusion), in customer reviews, blogs, fanzines, or on discussion lists, with a lot of respect for freelance, non-aligned, film criticism. Cult film takes a prominent place as a catalyser of this form of consumption. Since the mid-1990s, this process has become known as paracinematic consumption, and the resulting canon as paracinema. The term describes the complexity of the alternative canon constructed. The paracinematic attitude is one that finds ‘different reasons’ for enjoyment of cinema, outside accepted ‘good tastes’. So, a film appearing in the official canon of cinema, such as Citizen Kane (1941) or Battleship Potemkin (1926) can also appear in the alternative, cult canon, but judged by ‘differing’ standards. These standards usually involve the blurring of numerous categories, making the organising principles of the ranking and listing almost invisible and/or intangible. This obfuscation is exactly what paracinema aims for.

The final step in cult movie consumption is the construction of an Alternative Canon of cinema, pitched against the ‘official’ canon. Cult moviegoers not just consume but also champion a particular kind of film. This championing demonstrates itself in a variety of ways, but lists (see our own top 111 and personal top 25) are a typical characteristic of this. The Psychotronic Movieguide and numerous Cult Movies collections are key examples, as is the way in which a magazine like Fangoria established a canon in the 1980s. List-mania, to be found on virtually all websites devoted to cult cinema (and now in rapid adoption by online retailers) is the most visible feature of the alternative canon and partisanship of taste typical for cult cinema reception. Significantly, a lot of the canonizing is done amateurishly: in semi-communal circles (nerd circles, governed by rituals and exclusion), in customer reviews, blogs, fanzines, or on discussion lists, with a lot of respect for freelance, non-aligned, film criticism. Cult film takes a prominent place as a catalyser of this form of consumption. Since the mid-1990s, this process has become known as paracinematic consumption, and the resulting canon as paracinema. The term describes the complexity of the alternative canon constructed. The paracinematic attitude is one that finds ‘different reasons’ for enjoyment of cinema, outside accepted ‘good tastes’. So, a film appearing in the official canon of cinema, such as Citizen Kane (1941) or Battleship Potemkin (1926) can also appear in the alternative, cult canon, but judged by ‘differing’ standards. These standards usually involve the blurring of numerous categories, making the organising principles of the ranking and listing almost invisible and/or intangible. This obfuscation is exactly what paracinema aims for.

The Political Economy of Cult Film

A lot of cult films are produced for profit, so producers appreciate smooth planning and shooting, but something always goes wrong with cult films – there is always something unplanned intervening in the one of the levels of production, promotion, or reception that gives it the reputation it needs to become cult.

Production legends and accidents. Cult films are often the result of ‘accidents’. They invariably have complex, confused, controversial, or bumpy origins, wrought with smaller or bigger narratives (‘legends’, ‘myths’). They seem to happen, more than to be planned, even in the cases of generic cult movies, like Roger Corman’s exploitation movies shot on the fly such as Caged Heat (1974) or The Terror (1963). The murky and bizarre legends of their origin help form a basis for their cult(ural) presence. Even legendary auteurs whose work is seen as very consistent or planned seem to have the odd one out, and that is most likely to be a cult favourite (like Hitchock’s Psycho, 1960; or Rope, 1948). Filmmakers whose careers are littered with such accidents, and their accompanying legends, like Orson Welles (The Magnificent Ambersons, 1942) or Terry Gilliam (Brazil, 1984), are likely to be celebrated as cult figures, as are filmmakers whose ‘later’ films are so self-involved they lose all sense of reality, like Nicholas Ray’s We Can’t Go Home Again (1976). Brilliant failures and spectacularly ‘tanking’ films have good chance of picking up cult credentials.

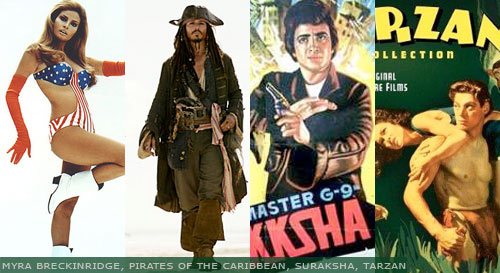

![]() Cult Stardom differs from regular celebrity culture. Cult stars often suffer major setbacks (personally as well as professionally) and their careers and lives are surrounded by mystery and tragedy. The sudden death of Rudolph Valentino, Bela Lugosi’s sad demise, the closet sexuality of Rock Hudson, the self-destruction of Judy Garland, and the excesses of Elvis Presley are key to their cult legend – leading to dedicated followings sympathizing with plights marked by addiction, abuse, or suicide. Such followings are not always free from campy or ironic irreverence. A quite separate category is the cult star known for one role only, most likely monsters, like Gunnar Hansen’s Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, a frequent feature at monster conventions, or self-aware sex symbols, like Raquel Welch in Myra Breckenridge (1969).

Cult Stardom differs from regular celebrity culture. Cult stars often suffer major setbacks (personally as well as professionally) and their careers and lives are surrounded by mystery and tragedy. The sudden death of Rudolph Valentino, Bela Lugosi’s sad demise, the closet sexuality of Rock Hudson, the self-destruction of Judy Garland, and the excesses of Elvis Presley are key to their cult legend – leading to dedicated followings sympathizing with plights marked by addiction, abuse, or suicide. Such followings are not always free from campy or ironic irreverence. A quite separate category is the cult star known for one role only, most likely monsters, like Gunnar Hansen’s Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, a frequent feature at monster conventions, or self-aware sex symbols, like Raquel Welch in Myra Breckenridge (1969).

Promotion: specialist events and limited access. Promotion campaigns will try anything to present a film as ‘cult’, from Barnum-like stunts to William Castle-type gimmicks. Still, in most cases a film becomes cult through a failure in effectiveness or containment of tested techniques (missed opportunities, messed up openings, unintended scandals). A good example is the ‘freak’ programming of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre as a 1970s children’s matinee movie. Next to that, specialist screenings and festivals play an important role. The 1970s circuit of midnight screenings that led to the cult reputations of El Topo, Eraserhead, or The Rocky Horror Picture Show is one example. Exploitation cineastes like Lucio Fulci and Jean Rollin, and the more edgy work of iconoclastic directors like Guy Maddin or Gregg Araki thrives on such circuits. The lack of availability often determines a film’s cult. The cult reputation of the ‘video nasties’ in the 1980s was directly connected to their unavailability in the UK. Other ‘inaccessible’ films include Zéro de conduite (1933, banned for decades), or Superstar: the Karen Carpenter Story (1987, blocked by courts). In some cases, a soundtrack is as close as one can get to a film, as was the case with Koyaanisqatsi (1982) for a long time. Even so-called blockbuster cults, such as Pirates of the Caribbean (2003-2007) or The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003), which are available in abundance, operate according to this mechanism of limited access – in this case the element of ‘rarity’ shifts back to specialist events like dress-up screenings or red carpet premieres, or elite merchandise.

![]() Reception: Tales and Tails. Though they often exist in the margins, cult films stick around forever in fetish markets where they maintain in constant demand. One important characteristic of this long tail reception is the constant stream of tales around a film. Scanners (1981) or Natural Born Killers (1994) for instance remained hotly debated for years after their release, becoming associated by proxy with several kinds of scandals. Such continuous presence often convinces producers there is room for serialization of franchises through sequels and remakes, all of which of course add to the attention the original receives. The numerous sequels to Friday the 13th (1980), including tie-ins with that other franchise Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), and the stream of Hollywood remakes of Japanese horror films, like Ring (1999) or Dark Water (2003) have given the originals an almost endless reception tail. In addition, retrospectives, restorations, revivals, re-releases, director’s cuts, spin-offs, rip-offs, and spoofs solidify their reception presence, making cult reception one of the most sought after reception conditions in filmmaking.

Reception: Tales and Tails. Though they often exist in the margins, cult films stick around forever in fetish markets where they maintain in constant demand. One important characteristic of this long tail reception is the constant stream of tales around a film. Scanners (1981) or Natural Born Killers (1994) for instance remained hotly debated for years after their release, becoming associated by proxy with several kinds of scandals. Such continuous presence often convinces producers there is room for serialization of franchises through sequels and remakes, all of which of course add to the attention the original receives. The numerous sequels to Friday the 13th (1980), including tie-ins with that other franchise Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), and the stream of Hollywood remakes of Japanese horror films, like Ring (1999) or Dark Water (2003) have given the originals an almost endless reception tail. In addition, retrospectives, restorations, revivals, re-releases, director’s cuts, spin-offs, rip-offs, and spoofs solidify their reception presence, making cult reception one of the most sought after reception conditions in filmmaking.

The Cultural Status of Cult Film

The way many films travel, often accompanied only by limited publicity campaigns can cause audiences to be unprepared for their themes and imageries, and unaware of their intentions. Cult films often seem to represent topics deemed unusual or inappropriate. At its least extreme, this simply leads to vague perceptions of ‘strangeness’, but in some cases they might upset cultural sensitivities, causing condemnation or even persecution.

Some films may seem ‘normal’ to their home cultures, but become Objects of Curiosity once they leave home, evoking wonder or hostility of a cultist kind. Hong Kong’s police thrillers (The Killer, 1988), Japanese manga films (Akira, 1988), Belgian realist horror (Man Bites Dog, 1992), blaxploitation (Shaft, 1971), or Bollywood films (Surakksha, 1979) are obvious examples of this. Films depicting, or set in, rarely viewed locations, such as rainforests of the poles, also attract curiosity. Werner Herzog’s Amazon films (Aguirre, 1972; Fitzcarraldo, 1981) make them stand out among other stories of exploration. In a few cases, films also find timely, often unintended, fits with issues high on the cultural agenda, giving them a pressing topicality. The Fly’s (1986) metaphors of sex and disease rang parallel to concerns about AIDS at the time, augmenting its cult status.

![]() A film’s Cultural Sensitivity is related to its cult reputation. Cult films often walk a blurry line between exposing and capitalizing on these sensitivities, regularly giving the impression they problematize as well as reinforce prejudices. It is a core reason for their appeal, and of course a point of contention. The most hotly debated sensitivities are representations of animal cruelty, misogyny, non-western ethnicities, or small-town mentality. Films containing animal cruelty are prone to bans in most countries, and as a result many only have a restricted availability. Le sang des bêtes (1949) is usually seen as an example that exposes animal cruelty whilst showing it, while Cannibal Holocaust (1980) was persecuted in several countries for exploiting it – hence it is more of a cult film. Claims of misogyny are often made against rape-revenge films, like Straw Dogs (1971), I Spit on Your Grave (1978), Baise-moi (2000), or Ichi the Killer (2001), with the films receiving praise for their boldness as well as criticism for their objectification of women. Similarly, the films of David Cronenberg (such as Shivers, 1975) and Dario Argento (like Tenebrae, 1982) are often perceived as insensitive in their representations of women – in most cases they are victims of gruesome acts of violence. The representation of non-western ethnicities as stereotypically mysterious, seductive, immoral, deceptive, barbaric, or savage is also a prominent feature of cult cinema’s cultural status, with Tarzan films (Tarzan and His Mate, 1934), mondo cinema (Mondo Cane, 1962) and exotic soft-porn (Emmanuelle, 1972) as prototypical examples. While such films are often criticized as racist, it is remarkable how they also exhibit a liberal attitude towards the breaking of cultural taboos, especially those surrounding sexuality, promoting ‘forbidden desires’ and fetishes. In much the same vein, films that mock, or brutally expose, the life in ‘backward’ rural communities within Western culture often receive cult reputations. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) is an iconic example, as are Deliverance (1972) or The Wisconsin Death Trip (2000). Again, while these films receive criticism for their unsalted depiction of such communities, they also attract praise for exposing the issues of class that underpin many considerations of rural life as brutal, cruel, simple, simplistic, or incestuous. House on the Edge of the Park (1980) is one cult film in which such class issues come to the fore.

A film’s Cultural Sensitivity is related to its cult reputation. Cult films often walk a blurry line between exposing and capitalizing on these sensitivities, regularly giving the impression they problematize as well as reinforce prejudices. It is a core reason for their appeal, and of course a point of contention. The most hotly debated sensitivities are representations of animal cruelty, misogyny, non-western ethnicities, or small-town mentality. Films containing animal cruelty are prone to bans in most countries, and as a result many only have a restricted availability. Le sang des bêtes (1949) is usually seen as an example that exposes animal cruelty whilst showing it, while Cannibal Holocaust (1980) was persecuted in several countries for exploiting it – hence it is more of a cult film. Claims of misogyny are often made against rape-revenge films, like Straw Dogs (1971), I Spit on Your Grave (1978), Baise-moi (2000), or Ichi the Killer (2001), with the films receiving praise for their boldness as well as criticism for their objectification of women. Similarly, the films of David Cronenberg (such as Shivers, 1975) and Dario Argento (like Tenebrae, 1982) are often perceived as insensitive in their representations of women – in most cases they are victims of gruesome acts of violence. The representation of non-western ethnicities as stereotypically mysterious, seductive, immoral, deceptive, barbaric, or savage is also a prominent feature of cult cinema’s cultural status, with Tarzan films (Tarzan and His Mate, 1934), mondo cinema (Mondo Cane, 1962) and exotic soft-porn (Emmanuelle, 1972) as prototypical examples. While such films are often criticized as racist, it is remarkable how they also exhibit a liberal attitude towards the breaking of cultural taboos, especially those surrounding sexuality, promoting ‘forbidden desires’ and fetishes. In much the same vein, films that mock, or brutally expose, the life in ‘backward’ rural communities within Western culture often receive cult reputations. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) is an iconic example, as are Deliverance (1972) or The Wisconsin Death Trip (2000). Again, while these films receive criticism for their unsalted depiction of such communities, they also attract praise for exposing the issues of class that underpin many considerations of rural life as brutal, cruel, simple, simplistic, or incestuous. House on the Edge of the Park (1980) is one cult film in which such class issues come to the fore.

Whenever a film is perceived as Politically Dangerous or ‘subversive’ it is more likely to become a cult. The Trip (1967), Le weekend (1967), Easy Rider (1969), and Zabriskie Point (1970), for instance, all share a positive representation of 1960s counterculture, often depicting dug taking, ‘deviant’ behaviour, alternative rock music, and political protest. British punk cinema, such as Jubilee (1978) and Rude Boy (1980) is another example of ideologically inspired cult film. A common tool in the politically inspired cult film is that of deconstruction, of breaking down the cohesiveness of official culture by exposing itsincoherencies and prejudices, and by celebrating ‘lapses, breaks, and gaps’ in its discourse. The tool has helped make the feminist genre films of Stephanie Rothman such as Terminal Island (1973) or The Working Girls (1974), and several adaptations of David Mamet’s attacks against political correctness, such as Oleanna (1994), or Edmond (2005) into cult films.